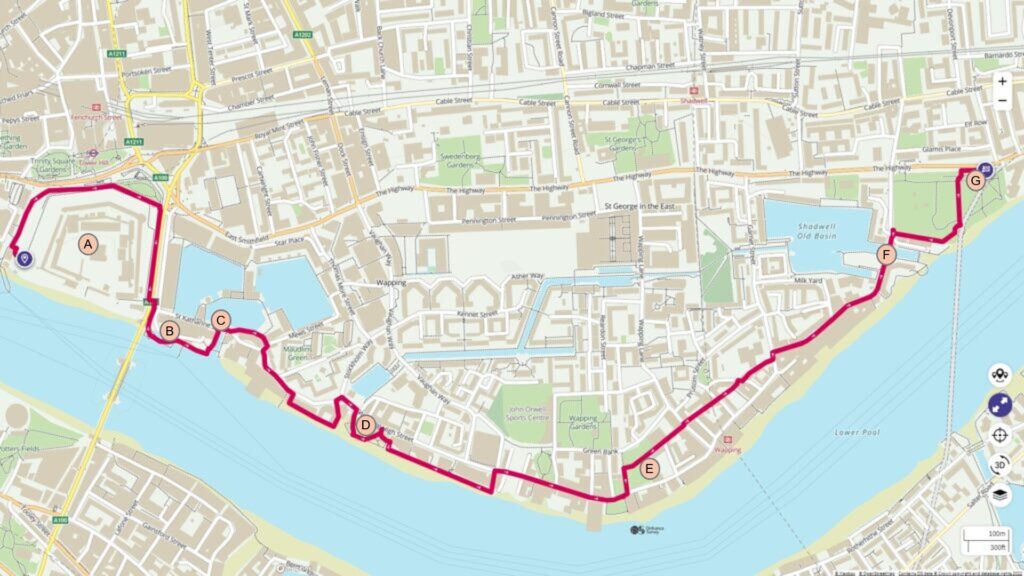

Follow the entire walk on . The route map is available on

.

B: Tower Bridge Close up

C: St Catherine Docks

D Hermitage Riverside Memorial Garden

E Waterside Garden

F Shadwell Basin and Bascule Bridge

G: King Edward Memorial Park

A: Tower of London

The Tower of London stands as a prominent monument, symbolizing England’s rich history and architectural prowess. Constructed by William the Conqueror in 1066, the White Tower was meant to assert Norman dominance, strategically positioned on the River Thames to serve both as a fortress and a welcoming threshold to the capital. This historical edifice is Europe’s most well-preserved example of an 11th-century fortress palace, showcasing a rare continuity of royal architecture that spans from the 11th to the 16th centuries.

It plays a critical role in the history of the City of London, serving both protective and controlling functions. The Tower of London not only safeguarded the city with its formidable defensive structures and garrison but also exerted control over its citizens. Emblematic of Norman power, the Tower signifies the extensive influence of the 11th-century Norman Conquest on England, fostering ties with Europe, and shaping the English language, culture, and monarchy.

As an outstanding example of Norman military architecture, the White Tower, along with its subsequent 13th and 14th-century additions, represents the zenith of medieval castle design. The evolution of the Tower from a fortress to a luxurious palace complex highlights its innovative and influential status in European castle development during the 13th and early 14th centuries.

Moreover, the Tower of London is closely associated with the development of key State Institutions, embodying roles critical to the nation’s defense, record-keeping, and coinage. Its continuous use by monarchs helped cultivate significant state institutions, with the Tower acting as a major repository for official documents and the Crown Jewels, underscoring its role as a royal fortress.

Historically, the Tower has been a central stage for pivotal events, from the imprisonments and executions of English royalty to its influence on the Reformation in England. These events have cemented the Tower’s iconic status, making it a symbol of power, innovation, and history.

B: Tower Bridge

Tower Bridge, a notable double-leaf bascule (drawbridge) type bridge, spans the River Thames, connecting the Greater London boroughs of Tower Hamlets and Southwark. It stands as a complement to the Tower of London, both in its aesthetic appeal and historical significance. Completed in 1894, Tower Bridge measures approximately 240 metres in length and provides a 76-metre wide opening. Its iconic twin towers rise 61 metres above the Thames, with glass-covered walkways between them that attract tourists for their views and historical context. Initially designed to enable pedestrian access even when the bridge was raised, these walkways were closed for a period due to unsavory activities but reopened in 1982. Until 1976, Tower Bridge operated on hydraulic pumps powered by steam, which, while now replaced by electric motors, are maintained and displayed for visitors. The bridge’s operation has become less frequent due to reduced shipping activity in the London Docklands.

C: St Catherine Docks

St. Katharine Docks emerged in the early 19th century, during a period marked by the end of monopolies granted to London’s docks, setting the stage for a new competitive era in the dock industry. This development near the Tower of London initiated a shift towards enclosed, tide-free docks in response to increasing trade through the Port of London and to counteract theft. Merchants, particularly those dealing in sugar and rum from the Caribbean, spearheaded this move to alleviate congestion on the Thames and protect their cargoes. The establishment of the West India Docks in 1802, followed by other specialized docks, reflected a burgeoning global trade facilitated by London’s strategic position.

The legislation allowing duty deferment on imports until they left the port transformed London into an entrepôt, a pivotal trade hub where goods could be transshipped duty-free. This boosted the volume of trade passing through London’s docks. The expiration of the monopolies granted to the early docks in the mid-1820s coincided with speculative plans for new dock developments, taking advantage of the imminent free trade environment.

St. Katharine’s area, with its rich history dating back to the early 12th century as a place of care under royal patronage, was chosen for the development of these new docks. This move marked a significant shift from the historical use of the Thames’ north bank wharves, which were becoming increasingly congested. The creation of St. Katharine Docks not only represented an evolution in London’s infrastructure to support its growing empire and industrial prowess but also a transformation of a historically significant district into a center of global trade.

D: Hermitage Riverside Memorial Garden

The development of Hermitage Wharf into a residential area was met with public demand for the preservation of riverside land as a public garden. Despite a design competition that yielded many proposals, financial constraints led to the realization of a garden that many consider to be of indifferent quality. This space is adjacent to a high-quality residential project by Andrew Cowan Architects at Hermitage Wharf. Critics argue that the landscape design fails to live up to its potential, presenting a lackluster appearance that contrasts sharply with the residential development. Suggestions were made that a more ambitious garden design could have enhanced the overall value of the development. The London Borough of Tower Hamlets is critiqued for allowing this outcome, and it is recommended that future projects consider successful examples of floodable riverside terraces, such as those in Varanasi, India, known for their exemplary waterfront landscape architecture.

E: Waterside Garden

Waterside Garden occupies the historic site of Execution Dock, where for over four centuries, pirates, smugglers, and mutineers were executed. The Admiralty Court conducted these hangings, ensuring that death came slowly through strangulation, as there was no trapdoor mechanism. Custom dictated that the bodies remain visible, submerged by three successive tides, serving as a grim deterrent to piracy. Despite the spectacle these events created, they seemingly did little to deter criminal activity at sea. The site, now transformed into a garden, once hosted these public executions, attracting large crowds and becoming a significant part of local lore. The narrative of Captain Kidd, one of the most infamous pirates executed here in 1701, remains intertwined with the history of the area and is commemorated in the nearby pub named after him.

F: Shadwell Basin and Bascule Bridge

Shadwell Basin, part of the historic London Docks, has transitioned from a bustling commercial dock to a housing and leisure complex in Wapping, London. Retaining its water body, unlike other parts of the London Docks, Shadwell Basin serves as a recreational area for activities such as sailing, canoeing, and fishing. The surrounding residential development, designed by MacCormac, Jamieson, Prichard, and Wright and built between 1986-1988, reflects the architectural essence of 19th-century dockside warehouses with its four and five-story buildings. In 2018, this development was recognized for its architectural significance and listed as Grade II by Historic England. The area includes notable features like the Benson Quay, Riverside Mansions, and the Monza Building, alongside the preserved Wapping Hydraulic Power Station building. A Scherzer rolling lift bascule bridge, restored in the 1980s, spans the basin’s entrance, adding to the site’s historical and functional richness. Shadwell Basin is a favored spot for cyclists, joggers, and pedestrians, offering scenic walkways alongside the water and connecting to other open spaces in the area.

G: King Edward Memorial Park

King Edward VII Memorial Park, situated in Shadwell, East London, provides a verdant retreat along the stretch between the River Thames and The Highway. Originating from a proposal to commemorate King Edward VII through the creation of a public park, its development was postponed by World War I, finally opening in 1922. The park exemplifies Edwardian design with a full-length terrace overlooking the river, central to which stands a monument to the park’s namesake. This space was designed to offer the sole extensive public riverside vista in the area from Tower Bridge to the Isle of Dogs at the time of its inception, catering to the recreational needs of the Stepney community.

Historically, the park has been enhanced with features like glasshouses, a bandstand, and playgrounds, providing a rich environment for local flora and fauna, as well as recreational spaces for the community. The park’s layout includes a significant riverside walkway, historically complemented by a shaft leading to the Rotherhithe tunnel, allowing for an uninterrupted walk under the Thames.

Currently, the park plays a role in the Thames Tideway project, aiming to improve London’s sewer system. This project is expected to extend the park’s green space into the Thames, encapsulating the construction site. Despite urban encroachments, King Edward VII Memorial Park has remained a cherished “green lung” for East London, offering a tranquil oasis and a recreational hub for generations.